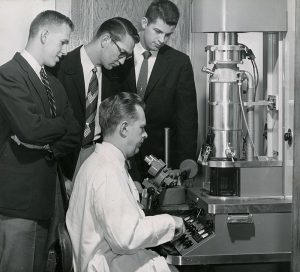

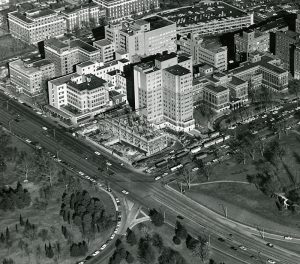

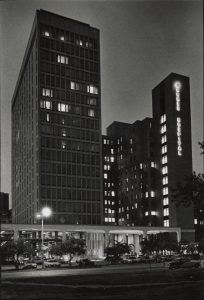

A new exhibit titled “That Was Then: An Architectural History of the Washington University Medical Center” is on display through Aug. 16 on the seventh floor of Bernard Becker Medical Library. Through a series of before-and-after photographs, the exhibit shows how the medical campus has changed over the past 100 years. One building in particular – Queeny Tower – dramatically altered not just the skyline but also the history of the medical center.

Even before it was completed in 1965, Queeny Tower became a flashpoint for conflict between Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes Hospital. A dispute over influence in the tower’s operation threatened the affiliation agreement between the university and the hospital.

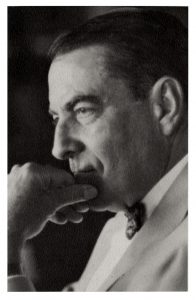

Communication broke down between two key players – Edgar Queeny, former chairman of Monsanto and president of the Barnes Hospital board, and Edward Dempsey, dean of the medical school. But out of the disagreement came a closer relationship between the School of Medicine and the hospitals of the medical center. It also created an opportunity for a young faculty member to become one of the most influential leaders in Washington University’s history.

In 1960, Edgar Monsanto Queeny retired as the chairman of Monsanto, the company his father founded. In 1961 he became chairman of the board of trustees of Barnes Hospital. A shrewd businessman, Queeny was troubled by the operating deficit at Barnes Hospital and the state of its facilities.

While the School of Medicine had constructed several new buildings for its clinical operations – Wohl and Renard Hospitals in the 1950s and the University Clinics building in 1961 – Barnes Hospital had not had a major addition since the Rand-Johnson surgical wing was constructed in 1929. The hospital was not earning enough revenue to keep up with the depreciation of its aging infrastructure. Thomas H. Eliot, the then-Chancellor of Washington University, later said that Queeny “decided that come hell or high water, he was going to make Barnes pay for itself.”

The university and Barnes Hospital agreed to cooperate on a capital campaign to raise money for both the School of Medicine and the hospital and began negotiating a new contract. The previous contract, signed in 1949, was overdue for renewal.

The backdrop to all of this was the rapidly changing landscape of American healthcare in the 1960s. Queeny, who was a member of Health Information Foundation, a think tank created to document and define areas in the health field in need of improvement, was perhaps more cognizant of the evolution of the cost structures of American healthcare – especially the rapid rise of “voluntary” or private health insurance – than the physicians and scientists who represented the School of Medicine.

Working through all of these issues with Queeny was Edward W. Dempsey, the dean of the medical school. Dempsey, who was also the full-time chair of the department of anatomy, had no clinical experience in a hospital setting.

At first, Queeny and Dempsey worked well together. In 1962, they were instrumental in creating the first organization to unify all of the institutions at the medical campus. Known as “Washington University and Associated Hospitals,” it consisted of the School of Medicine, Barnes Hospital, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, Barnard Free Skin and Cancer Hospital, the Central Institute for the Deaf and Jewish Hospital of St. Louis. It went by the unflattering acronym WUMSAH. (In 1972 it would be renamed “Washington University Medical Center.”) Though it was an important first step in coordinating the increasingly complex interactions of the medical center, it languished without clear leadership.

Soon differences of opinion over space planning went unresolved while misunderstandings about the allocation of funds from the capital campaign led to distrust. Queeny also initiated efficiency reviews and tried to close unprofitable clinics – mostly those which cared for indigent patients.

Then, when Queeny proposed that he select which doctors would have offices in the new Queeny Tower (albeit with the approval of the school’s medical faculty) Dempsey and many of the other members of the school’s faculty, many of whom were already angered by these other actions, were enraged.

At the heart of the issue was the difference in physician revenue sharing based on their full-time or part-time faculty status at the school. Full-time faculty received a salary for their efforts in teaching, research and patient care. Revenues generated from their patient care activities were chiefly earmarked as revenue for the school. Full-time faculty, since they received a salary, treated patients regardless of their ability to pay.

It was typical in medical education that the wards and clinics necessary for the training of student doctors would often operate at a financial loss. As the costs of operating these clinics increased, the losses became significant. Under the old contract with Barnes Hospital, most of these losses were borne by the hospital.

However, part-time faculty were private practitioners and not paid by the school. Since they did not earn a salary from the school they had more incentive to see private paying patients and the hospital garnered more of their revenue.

In order to maximize revenue for the hospital, Queeny proposed that a significant percentage of offices in the new tower would be held by the part-time faculty. The tower would also cater to a wealthier clientele of paying patients many with private or employer-subsidized health insurance. Many of the full-time faculty saw this as a crass grab for money and a repudiation of their commitment to their full-time positions.

Queeny recognized their concerns and, in a July 1963 memo titled “Annals of the Tower,” tried to express that his position should not be seen as a personal affront to the full-time faculty.

“The deterioration of Barnes-School relationship is due to the inclusion of the doctor’s offices in the Tower,” he wrote. “The Dean, Dr. Moore and others of the faculty object strongly to the presence of part-time men in the building. This is caused, in my opinion, by the greater earnings of the good part-time men than members of the faculty who serve for a modest salary. I have always [original emphasis] held to the view that the faculty are intelligent, dedicated men; and whether a part-time doctor had an office on Euclid Avenue or Kingshighway, should not affect faculty morale. Nevertheless, herewith is the story as our difficulties developed.”

Then in late 1963, Dempsey issued a report on the state of affairs. In it, he blamed all of the unresolved issues and the impasse that had developed on the staffing of the tower solely on Edgar Queeny.

Queeny responded in a carefully crafted rebuttal, citing documents and quoting Dempsey himself, titled “Notes Relevant to the Falsities in the Report of the Dean.” In closing, Queeny attacked Dempsey saying, “I am left to wonder, however – if one, to mislead others, dares create with a pen falsities which will lie in a record, what mischiefs will he venture with his lips alone?”

The result was a total breakdown in communications. Former Chancellor Ethan Shepley later said, “Two men who had been great admirers of each other now became so bitter in their personal relations that, literally, they found it difficult to sit in the same room.”

The animosity spilled over into other aspects of the school’s relationship with the hospital. Desperate to resolve the situation, Chancellor Thomas Eliot created a Committee of Four– composed of two members of the Washington University board and two from the Barnes board. They, in turn, brought in outside consultants to review the matter – Joseph C. Hinsey, director of the Cornell Medical Center, and John H. Knowles, chief executive officer of Massachusetts General Hospital. Both were graduates of the School of Medicine but were considered impartial with extensive expertise in the issues in hospital and academic cooperation. After an on-site visit in March of 1964, they returned to St. Louis to present their report on April 23, 1964.

They recommended organizational changes which would not only address the current impasse but would be in place to resolve any future differences. They called for a new executive position – a vice-chancellor for medical affairs to work with the school and hospitals while re-invigorating and strengthening the languishing WUMSAH.

However, the report was just a report. It still needed to be implemented and someone would need to fill the newly created position of vice-chancellor. Meanwhile, the dysfunction at the medical center became public news. In May and June of 1964, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch ran a six-part series on the situation. In it, reporter David B. Bowes pointed out, “Parties to the dispute agree the selection of the best available candidate for [the vice-chancellor] would be crucial.” The candidate “would have to be an administrator, teacher, physician and scientist,” one anonymous observer was quoted as saying, “and maybe some other things too.”

A temporary solution was found when Carl V. Moore, chair of the department of medicine and one of the most respected physicians in the county, was coaxed into taking on the role of the vice-chancellor for medical affairs for just one year. In his June 4, 1964, acceptance letter to Chancellor Eliot, he wrote he would “live for the day when I can give the job up.”

As construction on Queeny Tower began, uncertainty was still in the air. The disagreements which had led to the conflict now appeared to be fundamental and intractable differences.

Margaret G. Smith, professor of pathology at the School of Medicine, wrote in a letter to the Post-Dispatch, June 8, 1964:

“The statement is made [in the editorial of June 3, 1964] that ‘the fundamental conflict is between the teaching and healing functions of the combined institutions.’ This statement could not be more incorrect and misleading to the community. The teaching and healing functions are inseparable – the acquisition and transmission of the knowledge of disease, its prevention and cure in order to heal the sick. The fundamental conflict in question is between the inseparable combination of the teaching and healing functions and the business administration of the hospital housing and operational facilities now planned to resemble those of a financially orientated hotel catering to those with well-lined pocketbooks.”

It was clear new leadership would be needed to move the medical center forward. In 1964, Dempsey resigned from the deanship and found a place in President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration as special assistant to the secretary of health, education, and welfare. He would eventually finish his career with positions at Columbia University and at Stanford.

Later in 1964, the head of surgery, Carl Moyer, also resigned. In his resignation letter, he said the Barnes leadership – especially Queeny – “have repeatedly demonstrated by administrative acts that what I am and what I stand for – namely full-time service to medical education and practice – is antithetical to their view of what the social order of medical education and service should be. … [They] look upon the full-time staff as an evil or inept body of men that contributes nothing to the hospital and is unworthy of any consideration. …”

Barnard Jaffe, a surgical resident at Barnes at the time remembered, “I was between operations and finally getting a bit to eat in the hospital cafeteria, when Carl Moyer came in and sat down next to me. … ‘Do you know what I’ve just done? … I’ve resigned.’ And he sat there for two hours – he would not let me leave – talking about why he resigned. He needed to get it off his chest, … He talked about the part-time/full-time problems; he talked about hard money and soft money. … He told me that the difference between the full- and part-time faculty incomes were enormous. He just emoted.”

But Carl Moore had made some progress. He successfully worked with Queeny to create a new 30-year contract between the school and hospital – though he later told an associate that negotiating with Queeny had taken 10 years off his life.

Also, M. Kenton King, assistant professor of medicine and preventive medicine was tapped to become the new dean of the medical school. King had been associate dean and chair of the admissions committee under Dempsey and had been acting dean in his absence. Carl Moore said of King, “He has enjoyed the respect of the faculty for a long time and … has impressed everyone with his leadership and his quiet, effective way of getting things done.”

The selection of Moore’s replacement as vice-chancellor would prove to be an inspired choice. In 1965, it was on the suggestion of Nobel Prize winner Carl Cori that a young assistant professor who had worked in Cori’s lab, William Danforth, was offered the job of vice-chancellor.

James S. McDonnell, the chair of the Washington University Board of Trustees invited him to dinner. Danforth later recalled than McDonnell “began talking about many things and then he began talking about creativity and how some scientists think all creativity is in the laboratory. He said, ‘You know, getting people to do the right thing, there’s a lot of creativity in that.’ He began spinning out visions of a team working together, talking about it and after a while I was hooked.”

Danforth was admittedly green but accepted the position. “I wasn’t really too interested at first, but I got hooked by Mr. Mac,” he said. “And there really was a crisis. I revered the medical school and thought something had to be done and I really thought I could make a difference.”

One of his first tasks was to be introduced to Edgar Queeny. “Carl Moore had done a lot to calm the waters. He took me to meet Edgar Queeny, I remember the first time and Carl said ‘Edgar, I want you to meet Bill Danforth’ I said: ‘Hello, Mr. Queeny.’ He said: ‘Call me Edgar.’ I said: ‘Okay, Mr. Queeny.’ Then we sat for about five minutes, nobody said anything. Carl got up politely and said: ‘It’s been nice visiting with you Edgar’ and we left. That was what Edgar Queeny was like. Edgar then invited me to go to the baseball game with him. … It was almost total silence during the trip down and then we sat together. Edgar wasn’t uncomfortable by silences and occasionally he’d say ‘good play.’ We got along okay. I came to appreciate Edgar and to like him.” Danforth would work with Queeny to forge closer ties within the medical center until Queeny’s death in 1968.

Danforth remembered, “You know, we were making peace with Edgar. When he became ill, I spent time with him. … He was no push over. He was a tough opponent. Most people who get into these voluntary positions want to do the right thing. That’s why they do it. He just saw the world a lot differently than Ed Dempsey did.”

In 1971, due to his leadership as vice-chancellor, Danforth would become the 13th chancellor of Washington University.