Nobel laureate Rita Levi-Montalcini was born in Turin on the 22nd of April 1909. She was one of 4 children, 3 girls and 1 boy, born to Adamo Levi, a gifted mathematician, and Adele Montalcini, a skilled painter. While both parents were considered highly cultured and had a strong appreciation for intellectual pursuits, certain educational opportunities were withheld from Levi-Montalcini on account of her gender. She recounts, “The four of us enjoyed a most wonderful family atmosphere, filled with love and reciprocal devotion. Both parents were highly cultured and instilled in us their high appreciation of intellectual pursuit. It was, however, a typical Victorian style of life, all decisions being taken by the head of the family, the husband and father. He loved us dearly and had a great respect for women, but he believed that a professional career would interfere with the duties of a wife and mother.” Therefore, Adamo decided that his 3 daughters would not enroll in University nor take interest in studies that would lead towards a professional career path.

However, when it became apparent to twenty-year-old Levi-Montalcini that she could not adjust to the feminine role her father desired for her, she sought his permission to pursue a professional career. Once received, Levi-Montalcini spent a mere eight months filling her knowledge gaps in Latin, Greek, and mathematics in addition to graduating from high school, before entering medical school in Turin.

She graduated summa cum laude in Medicine and Surgery from University of Turin Medical School in 1936, the same year that Benito Mussolini issued the Manifesto per la Difesa della Razza. This fascist manifesto created a foundation for laws that prevented non-Aryan Italian citizens from continuing their academic and professional careers. Forced to choose between emigrating to the United States or pursuing a study that did not rely upon support from the surrounding Aryan environment, Levi-Montalcini installed a miniature research lab in her bedroom where she conducted research inspired by a 1934 article by Viktor Hamburger reporting on the effects of limb extirpation in chick embryos.

Levi-Montalcini completed her degree specialization in neurology and psychiatry in 1940, and a year later she was forced to move to the country to continue her experiments due to the heavy bombing of Turin from the Anglo-American air forces. Before the war ended, Levi-Montalcini also worked as a medical doctor charged with the care of an Italian refugee camp where epidemics of infectious diseases and abdominal typhus were commonplace.

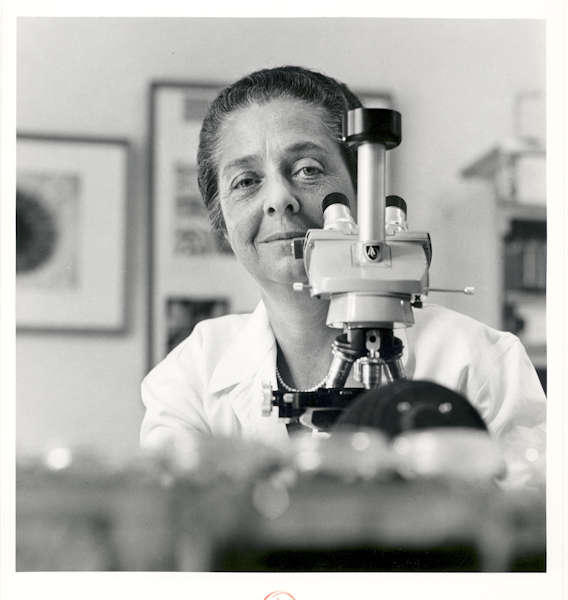

A couple years after the war ended in Italy, Levi-Montalcini accepted an invitation from Viktor Hamburger, who was then head of the Zoology Department of Washington University Saint Louis, to collaborate on further research. While she had only planned on staying in Saint Louis for a maximum of twelve months, she ended up staying for thirty years, eventually becoming a full professor of Zoology in 1958.

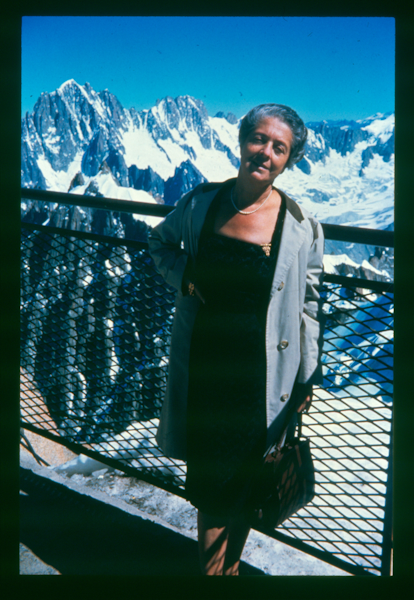

In the early 1960s Levi-Montalcini began dividing her time between St. Louis and Italy. She established a laboratory at the Higher Institute of Health in Rome, which participated in a joint research program with Washington University from 1961 to 1969. In 1969 she established the Laboratory of Cell Biology of the Italian National Research Council in Rome, serving as its director until 1979, and then as guest professor. In the mid-1960s the Washington University Zoology Department was incorporated into the Biology Department. Levi-Montalcini retired as professor emeritus of Biology in 1977.

Rita Levi-Montalcini shared the 1986 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with biochemist Stanley Cohen for their discovery of nerve growth factor (NGF), a protein that causes developing cells to grow by stimulating surrounding nerve tissue. Their research, conducted in the 1950s while members of the faculty of Washington University, was of fundamental importance to the understanding of cell and organ growth and played a significant role in understanding cancers and diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

With her sister Paola, Rita Levi-Montalcini established the Rita Levi-Montalcini Onlus Foundation, which focuses on educating young African women by providing study fellowships. In 1999, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations named Rita Levi-Montalcini one of its first four FAO Ambassadors, to help in its campaign against world hunger. In August 2001 she was appointed as senator for life by the then President of the Italian Republic, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi. Levi-Montalcini was a founder and former president of EBRI (European Brain Research Institute) which was established in 2002 to study the central nervous system – from the neurons to the whole brain – in health and diseases.

Levi-Montalcini has received numerous accolades in addition to the Nobel Prize as well. In 1963 she was the first woman scientist to receive the Max Weinstein Award, given by the United Cerebral Palsy Association for outstanding contributions in neurological research. In 1975 Levi-Montalcini became the first woman to be installed in the Pontifical Scientific Academy. She was a recipient of the International Feltrinelli Medical Award of the Accademia Nazionale die Lincei, Rome (1969), the William Thomson Wakeman Award of the National Paraplegia Foundation (1974), the Lewis S. Rosentiel Award for Distinguished work in Basic Medical Research of Brandeis University (1982), the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize of Columbia University (1983), the Ralph W. Gerard Award of the Society for Neuroscience (1985), the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award (1986), and the National Medal of Science (1987). She was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1966), the Potifical Academy of Sciences (1974), the American Philosophical Society (1986), as well as having received several honorary degrees in medicine and biomedical engineering. She also played a pivotal role in issuing of the Trieste Declaration of Human Rights and the 1993 foundation of the International Council of Human Duties at the University of Trieste. This is not an exhaustive list of her accomplishments.

If you would like to know more about this extraordinary human being, spend some time poking around our archives or request her autobiography, In Praise of Imperfection: My Life and Work (Basic Books, New York, 1988), from our library.

Rita Levi-Montalcini died in Rome on the 30th of December 2012.

Information for this blog post was compiled from an earlier digital exhibit bio by Ellen Dubinsky, previous archivists’ notes on the Becker Archives Database, and Rita Levi-Montalcini’s bio page on the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine’s website: nobelprize.org (2023). If you would like help finding what information the Becker Archives has available on Levi-Montalcini, you may schedule an appointment in our reading room, or contact archives staff at arb@wusm.wustl.edu. The Archives is located on the 7th floor of the Bernard Becker Medical Library.