“I came here with kind of the idea of opening up doors and trying to get the school involved in doing things for minorities” – Julian Mosley, MD, 1990

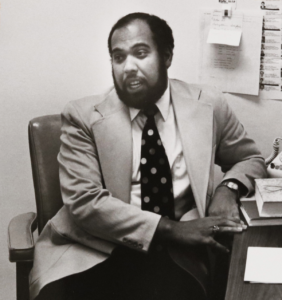

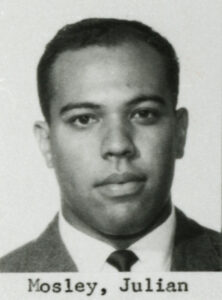

As a student at Washington University School of Medicine, Julian C. Mosley, Jr., MD, was instrumental in advocating for Black students. In the in the late 1960s and early 1970s, even as a medical student himself, Mosley worked to recruit Black students, tutored students who enrolled, and pushed the administration to provide institutional support for Black students and students from other historically disadvantaged groups. Following his graduation from WUSM in 1972, Mosley did his internship and residency at Jewish Hospital, where he was the first Black doctor to be chief surgery resident. He went into private practice in 1977, first with Frank O. Richards, MD, and then as a solo practitioner.

Mosley is one of the people who was featured in Becker Library’s recent exhibit, In Their Own Words: Stories of Desegregation at Washington University Medical Center. The exhibit highlighted the experiences of Black people and their allies who faced institutional racism and fought for change at the School of Medicine and its associated hospitals. Along with letters, photos, architectural plans, and other documents, the exhibit featured quotes from oral histories with doctors, nurses, students, and administrators who experienced segregation and advocated for change.

The exhibit included a quote from a 1990 oral history interview with Julian Mosley, but there’s much more to Mosley’s story—and his impact on the School of Medicine—than we could fit in the exhibit.

Read on to learn more about Mosley and listen him talking about his experiences in clips from his oral history.

On Encountering Prejudice at the School of Medicine

A native of East St. Louis, Illinois, Mosley entered the School of Medicine in 1968 with only two other Black students, Karen Scruggs, MD, and Patrick Obiaya, MD. He said his experience at the School of Medicine was similar to his experiences attending other predominantly white institutions in the 1960s, and it was difficult.

“People have some preconceived notions about what that [being Black] means, like, even though I’d had a lot of advanced education people felt that we weren’t going to do well in the school. And they felt that, you know, Blacks would always be inferior, of course, [as] physicians and stuff. There was a lot of prejudice at Wash University [School of Medicine] just because of the institution and the longevity of the thing, you know, it’s a prestige institution. Even though there had been Blacks who had attended places like Harvard [University] and done really well, nobody had ever attended here. The white population in general just had the preconceived notion that Black folks weren’t going to do as well. And I think, therefore that was a driving force for us to try to do as well as we could.”

On Recruiting Black Students

Beyond doing well in medical school, Mosley and his classmates were determined to increase the number of Black students at the medical school and support them.

“We worked in the dean’s office, we accumulated a number of names of predominantly Black schools which Washington University had never even made gestures toward, inviting their applications and so forth. We compiled a list of predominantly Black schools. Compiled a number of Black students who were making applications across the country. We started talking about some things to try to — first of all, increase the number of Black students at this school, increase the number of Black students across the country in majority [white] schools.”

While the work Mosley and other students did in the dean’s office was important, Mosley says one of the most “intelligent” things they did was to convince the administration that the work they were doing couldn’t be done effectively by students or by someone on a part time basis. Their advocacy laid the groundwork for the school to hire Robert Lee in 1972 as a coordinator—and later assistant dean—of minority affairs.

On Tutoring First Year Students

Another one of the ways Mosley and other students provided support was by tutoring first year students.

“…[P]eople in our class were very socially active. … As soon people realized that we were trying to get more minority students, a whole bunch of my classmates volunteered to be tutors. They helped organize the tutorial program, even before the instructors had a tutorial program in place, we had a tutorial program in place among the students to help the freshman students.”

On Interviewing Prospective Students

Later, Mosley became an ex officio member of the admissions committee and helped interview Black students, and became a long-standing member of the committee, even after he graduated.

“…[I] talked to them and encouraged them to apply here, telling them what we were trying to do, telling them what a quality school this was and trying to tell that … you’ll encounter prejudice wherever you go. So if you are Black in whatever school, if you are in a majority [white] school you are going to encounter prejudice. So if you are going to encounter prejudice at University of Missouri, you might as well encounter it at Washington University and try and then be in a position where you may be a leader in the future and be able to break down that [prejudice] in a more effective way.”

In fact, one of the students Mosley successfully recruited was Will Ross (MD ‘84), who joined the medical school faculty in 1996 and is the current associate dean for diversity at the School of Medicine.

Want to Hear More?

If you’d like to hear more from Mosley’s interview, check out the full transcript and audio of his oral history in Becker Library’s Digital Commons. While you’re there, you can access other oral histories in the Washington University Medical Center Desegregation History Project from more people who were influential in the process to desegregate the School of Medicine.