Nowadays, if you hear the term “animal magnetism” being slung around you’d probably understand it to mean that someone has a high level of charisma or sexual attractiveness, but a few centuries ago, the meaning was very different.

Eighteenth-century Europe was a hub of new ideas as the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution changed how people thought about the world. Older mystical traditions and philosophical thoughts collided and mixed with newer ideas about science as people continued to investigate the natural world and the way things worked. One idea that rose out of this maelstrom was animal magnetism, touted as a new means of curing human ills through the use of, as the name suggests, magnets.

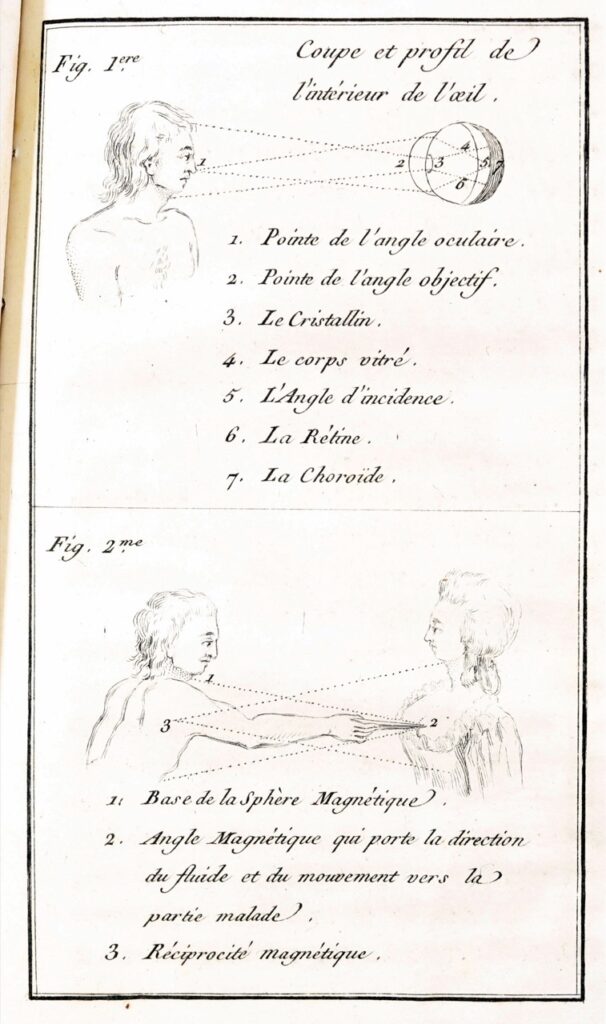

Animal magnetism was the late 18th-century brainchild of German physician Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815). Also called mesmerism, animal magnetism reflected the zeitgeist of the era. Although it was secular in that it avoided the explicitly religious, it was still a method of treatment that relied on harmony with nature and was dependent on unseen forces. It was scientific and new, but still somewhat mystical. The theory and treatment, based on Mesmer’s idea, claimed that there was a universal “magnetic fluid” or force that could be found in, and have a physical effect on, all living things. Therefore, by manipulating this fluid with magnets, one could manipulate the body into being well again — a universal cure for any disease.

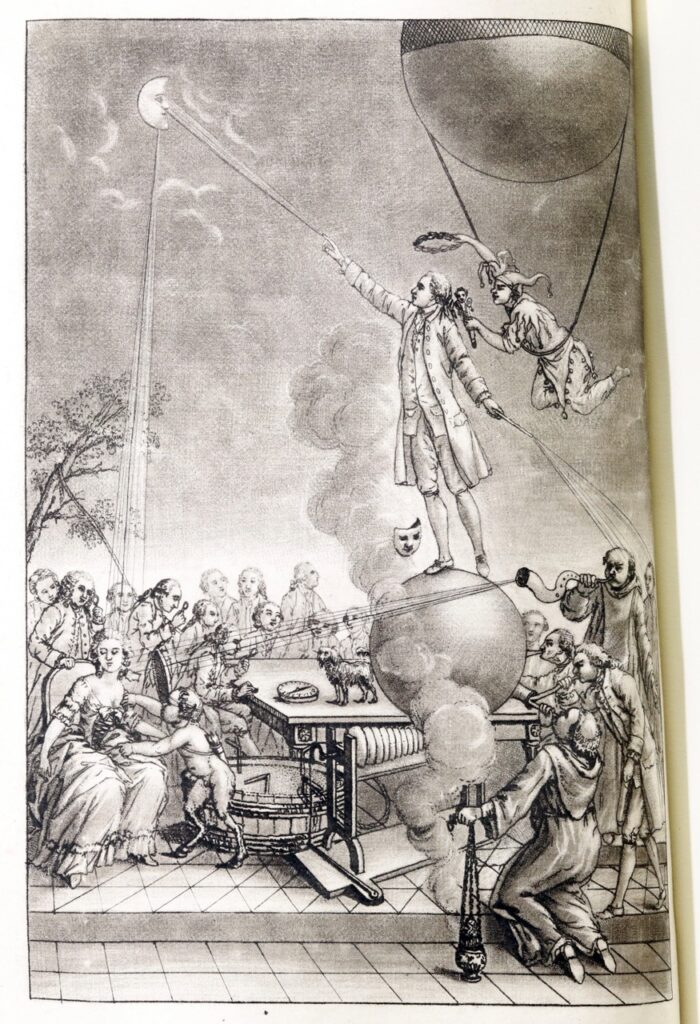

Mesmer was unpopular in Vienna but quickly grew a following in Paris, a city hungry for the latest scientific advancements and fads of modernity. Through the use of magnets and the manipulation of the magnetic fluid, Mesmer was able to affect patients without physically touching them. He claimed that he could produce pain and jolts through walls or people, even at a distance, and was seemingly able to cure a wide variety of conditions with this one method. Due to his popularity, he expanded his methods to also include mass forms of treatment.

Having won over the populace Mesmer then turned his eyes toward validation by either the Royal Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society of Medicine, or the Faculty of Medicine, but he was unable to convince the members of animal magnetism’s efficacy. Eventually, his popularity concerned King Louis XVI, resulting in the creation of the Royal Commission to formally refute or validate Mesmer’s claims. This was a joint commission between five members from the Royal Academy of Sciences (including Benjamin Franklin) and four members from the Faculty of Medicine.

At this point there were others — either disciples of Mesmer or those merely following in his footsteps who also practiced animal magnetism — but the purpose of the Royal Commission was to investigate animal magnetism itself, not its individual practitioners. Their primary goal was to prove the existence of the magnetic fluid and then investigate the uses of animal magnetism. As one can imagine, this proved to be difficult as the magnetic fluid was an intangible substance or force and thus had no measurable physical properties or means by which it could be detected by one’s senses. Ergo, the magnetic fluid espoused by Mesmer could only be observed via the effect it had on living creatures.

Through a series of controlled experiments, the commission decided that the effects of animal magnetism and mesmerism were a product of the power of suggestion rather than Mesmer’s magnetic fluid. Those who believed they would fall into a trance or expected to feel some sort of effect were then more likely to claim they were under the effects of animal magnetism. Similarly, those who expected these effects claimed to feel the effects when told the treatment was underway, even when nothing was actually being done. As a result, the Commission concluded that it was the subjects’ expectations and imaginations that were the force behind the effects of animal magnetism.

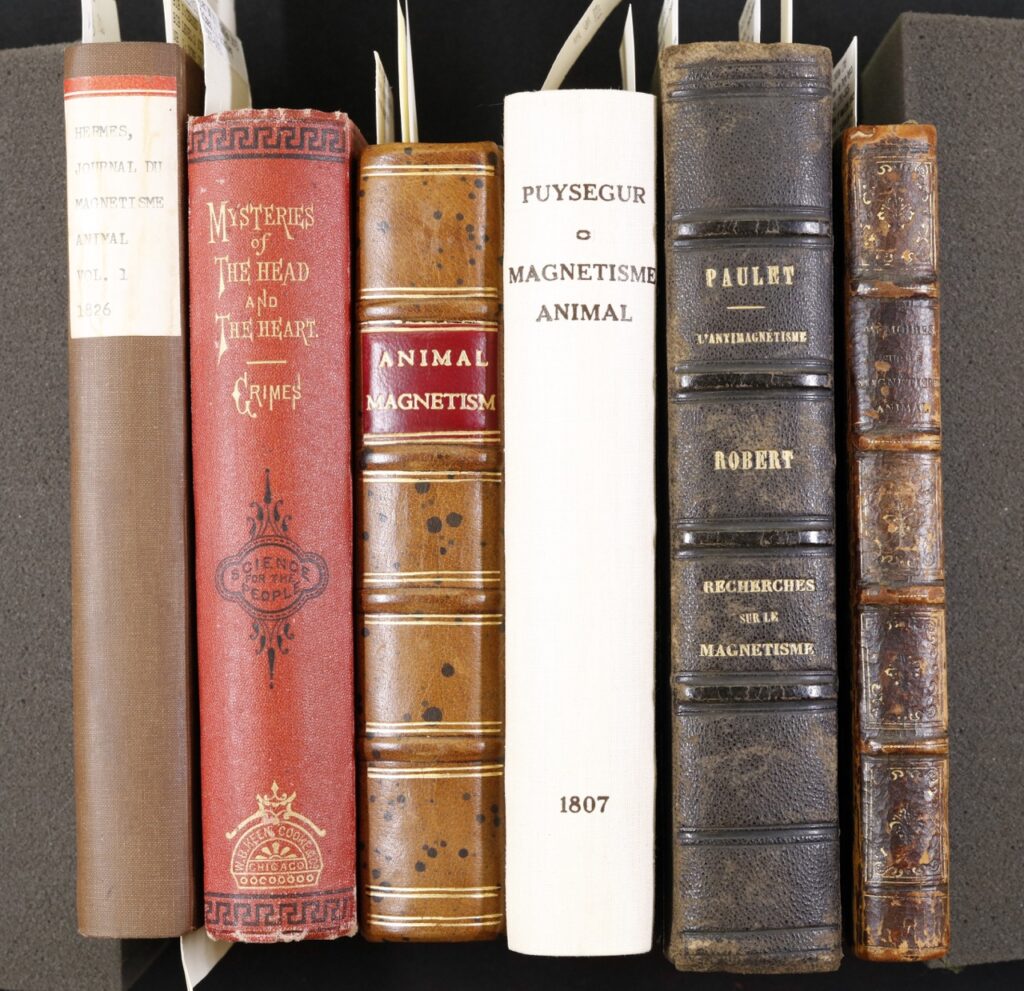

Ultimately, the commission released a report in 1784 that destroyed much of Mesmer’s credibility and support. By the end of the century, animal magnetism had mostly fallen out of favor. Yet the treatments were not completely without power. Franklin and the rest of the Commission conceded that even if it was the power of the patients’ minds rather than animal magnetism, these treatments were still able to cure conditions that had no other cure at the time. However, they cautioned against using such treatment freely since the magnetizer or mesmerist could potentially do more harm than good. Animal magnetism eventually saw a revival (as well as its fair share of deniers) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, we can trace concepts such as hypnotherapy to animal magnetism.

Reference and Further Reading:

- Haller, John S. Swedenborg, Mesmer, and the Mind/Body Connection: The Roots of Complementary Medicine. Swedenborg Foundation, 2010.

- Whitaker, Harry, et al. Brain, Mind and Medicine: Essays in Eighteenth-Century Neuroscience. Springer US, 2007.